The Art of Scripting

Is writing code an art form or an artisan activity? Is it art or a technological skill? Codes and algorithms instead of paint and brushes. The hybrid discipline of ARCHineering is coming, but before examining this hybrid, one needs to consider the origins of engineering. We should look at how engineers position themselves, because while the knowledge and practices of engineering date to the earliest settlements in history, the profession does not.

The discipline of engineering was first recognized as a discrete discipline when it was institutionalized as a separate faculty at Czech Technical University in Prague in 1707. The mythology of the discipline expanded to other fields including military and civil engineering, appropriating from the role of the architect as it went. The authority of the discipline grew and reached a summit by the 20th century.

The current hegemony of engineering has made it difficult for the layperson to discern among and evaluate the competencies of architects and the value that they add, vis-a-vis those of engineers. The general perception is that engineers are concerned with static loads and the resistance of a building to gravity and movement, while aesthetics and function fall within the domain of architects. In many sectors, the services of an architect are waived altogether; engineers are commissioned with designing a structure and interior designers with fitting it out.

In the 21st century, as digital design and production methods advance, this conflict will come to an end and the whole process will again be placed in the hands of a single professional, whose cardinal technical skill will be coding. This change in the role of the architect – or the ARCHineer – will be a preparation for another change in production modes yet to come. Later in this century, assembled buildings will give way to organic buildings that grow and habituate themselves. These buildings, supported by a multifaceted artificial intelligence, will be able to adapt according to the requirements of their occupants. Static structures will become dynamic ones.

Currently, in the GAD office, we are engaged in the entertaining game of evaluating our own work. What approaches and patterns do the buildings we have designed and constructed as a team have in common? Could software be written that is capable of initiating new such designs? Could we put together an open-source library of artificial intelligence that is capable of responding to the needs of different locations and climates and of the low or high buildings? Furthermore, is there some subtle common denominator or behavioral pattern in our approach to design? Or is it made up as we go along, contingent on our mood?

At first glance, I find it difficult to identify a common denominator in the designs, projects, and buildings that I have completed individually, together with colleagues in my office, or in other partnerships. Sometimes they even seem to have been designed by different authorial hands that makes life difficult for the architectural historian or critic. In terms of style, we chose this path. There are architects whose work is instantly recognizable, and they, too, deliberately chose their path. So why did we not choose the latter?

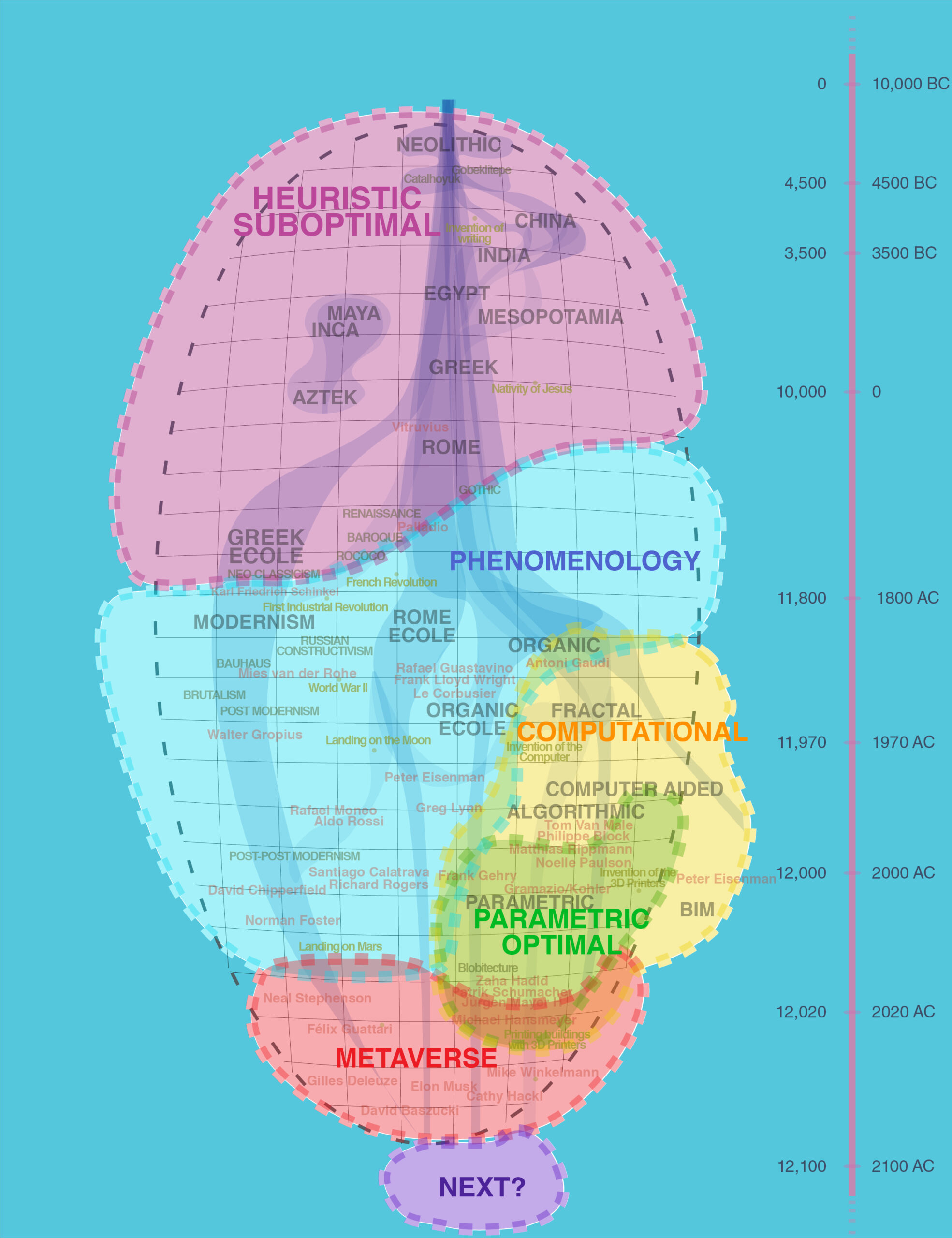

To answer this, I have discovered a correlation among architecture history, the history of my own development as an architect, and the process by which my projects develop. Where did I begin? Where are we now? And how does the future look? I think of these three questions as:

THESIS » ANTITHESIS » SYNTHESIS

Thesis

The art of building progressed in tandem until the end of the 19th century. It is in this period, which I call the “thesis era”, that first principles were established. The same construction techniques, patterns, and materials were being used throughout the world – buildings of earth and wood and later fired brick, stone, steel and other alloys.

Until the end of the 19th century, there were reasons behind the decision to settle in a place: fertile soil, defensible geography, and adjacent waterways. Buildings were built where there was the greatest benefit and were only destroyed by disasters like fires, earthquakes, floods, or wars. When a building was demolished, most of the materials could be reused. New buildings were constructed – still with natural materials – only when new techniques were developed or new functions necessitated them.

I think the necessary explanations regarding this section were given in previous chapters. The main question of this section is: why don’t we build with the old forms?

Antithesis

The 20th century is rife with works that are contrary to the disciplines, teachings and habits mentioned above. There were great leaps forward in engineering that brought easy and fast solutions to our daily lives. They had reflections on architecture as well.

Load bearing elements and claddings developed independently. Ease of construction rather than rigorousness informed these new structural skeletons, which were in turn draped with unrelated finishing materials. This poorly considered “flexibility” led to eclectic approaches to the design of buildings. When the load bearing elements were separated from the claddings at first this seemed like a freedom for the architect to realize his/her ideas in building forms. However, at the end of the century resulted in mostly banal, cheap, ugly buildings. For architects, the separation of structure and the envelope has also led to a system of education and training that focuses on the latter, that teaches that the envelope is the canvas for architectural expression. Structure, on the other hand, falls outside of the scope of the architect’s work and in the domain of the engineer who calculates and approves its arrangement.

Up until the end of the 19th century the primary concern of those involved in the built environment was protection against the adverse effects of natural phenomena such as earthquakes, landslides, floods, extreme climatic conditions, rivers and seas, and man-made disasters such as wars and fires. It was all about resilience, durability – at least until the time that buildings started to be demolished.

We look at the built environment from the perspective of its durability in time and the extent to which it responds to human needs. The approach to this in the 20th century was high-handed. More durable building materials and techniques were developed during this era, yet the life span of buildings is not defined by just these objective attributes but by criteria of a subjective nature. What I mean here is not the advantage of buildings that are deemed holy because of their function or program such as religious buildings to protect themselves from being destroyed by people.

I have not made any buildings of worship or religious purpose hiding behind this advantage; I refused the offers as much as I could. From time to time, not being able to hold myself together I might have made some trials but they have not been carried out to the end. These types of buildings have the advantage of protecting themselves from human destruction. I am aware of this advantage but I don’t force myself to design in an area I don’t believe in.

Enough of these buildings have been made in the world and of course among those there will be some that are significant examples of great architecture that impress us and leave their marks today and on the future.

Today even if a religious building is architectural rubbish or a structural monstrosity, its self-protection advantage steps in as it stands out like a sore thumb and it continues its existence regardless. One could say “You do better then.” Here the matter of belief comes into play for me. To me, a well-designed waste disposal facility could be holier than a cathedral or a mosque regarding its purpose.

We’ve written about what we do in architecture extensively; let’s elaborate on what we wouldn’t do and also won’t do; factories that violate animal rights, munitions factories, prisons, building projects that do not care about or even consider social and cultural responsibilities, government administration buildings with dictatorial briefs, industrial facilities that do not treat toxic wastes generated during production or produce a toxic waste that cannot be treated… I can’t recall all of them right now, but this list may expand in the future

Losing the purpose for which they were designed, undergoing alterations in time, or changes to the value of the land on which they sit – making it lucrative to replace a building with a larger, taller one – all potentially affect their longevity. Buildings only stand a chance of adaptive reuse if they have some symbolic value that renders them a cultural landmark. Or they may survive if new structures can be added beneath, adjacent, or above them, but while such additions could be respectful and attractive, the responses are often aggressive and inattentive.

I often hear this question from the public outside of the profession of architecture: “Why are the buildings, streets, and cities which were built before the end of the 19th century more beautiful than what is being built today?” I have periodically forwarded this question to pioneers and leaders in my profession, and their answers are always the same. Those were the buildings of the few, the distinguished, and the elected, counts, barons, dukes, landlords, pashas, and feudal lords; they were built on the back of slavery. Well then, should we choose architecture or humanity? Modernist architecture as a political view…

When I was young, I watched as youth from conventional families to whom I looked up to turned to socialism and later turned violent, disguising their local culture and prejudices (that they were never quite able to shed) as a global vision.

When I began undertaking small-scale projects, I wanted a better understanding of how architecture operates on a global level. I contacted renowned architects, into whose offices I would never have imagined entering, even from the back door, to ask to interview them. I conducted enough of such interviews to get started on a good path, and although I did them for my self-development, many were published. I never had the time to curate my archive of interviews, and as I progressed as a professional, they became less relevant. But I wish that when I was still a young, inexperienced architect that I had done more. When I proposed to these eminent architects to take their time with nothing to offer in return, their answer was invariably yes. They gave me a chance for an interview and shared their professional secrets with me, which was a once in a lifetime opportunity. This strategy is still valid, and I recommend young architects to pursue such prospects.

During one of these interviews, Jean Nouvel refused to let me photograph and publish the construction of the on-going Euralille project. He was aware of the fragile illusion of modern architecture: until the last pane of glass is mounted in place, the architecture appears flawed, vulnerable, and even disastrous. We would be hard pressed to find a surviving door or window in a classical Greek and Roman ruin or even in a 19th century masonry building, but the beauty of the architecture is indisputable. This begs the question whether glass, frames, and windows are necessary elements of architecture. How can I make them invisible?

When working on the reconstruction of Esma Sultan, I observed that a double skin created a meaningful architectural effect from both the exterior and interior. The most beautiful buildings are those where new interpretations of an old structure are held in balance. A combination of old and new…

The conceited and smug architects of the 20th century have exaggerated the separation of envelope from structure, have also disengaged the practice of architecture from the culture, knowledge, and buildings of the past from the streets and the city. Instead of processing the strictly ordered and no longer fashionable buildings of the past, it has become commonplace to demolish and start from scratch. However, architecture has always been concerned with using what already exists and is already available. The design approach we adopted at Esma Sultan would not be possible for a new construction, because the skins and load-bearing elements and suspended ceilings of 20th-century buildings are all designed and function independently.

The outer shell of the building dates back 200 years. While the new core was designed separately and functions independently, its articulation as a double skin puts the old and new into dialogue, conveying their contrast. (pls. see balance suspensions mounted in the gap page …) By combining the old and the new in a double facade, it results in a beautiful juxtaposition.

Interestingly, during the 20th century, all sides of the political spectrum agreed that production and reproduction lead to happiness. We wanted to produce fast and consume fast. However, concepts like democracy, human rights and equality were not met with the same, rapid response. The world did not unite within a worldwide federation under a single flag or share the same values. The election systems of countries governed by very different democratic systems were often manipulated by their current or elected local governments. The pandemic taught us a failure, distress, problem, disease experienced in one country can now spread around the world with lightning speed. We cannot say anymore that the internal affairs, decisions, governments, gravitas of the countries are solely theirs. In this century, the superiority of the wealthy and powerful may be waning, but housing issues and starvation still exist. Even into the 21st century, we must still think about how to resolve these issues.

Synthesis

“The Twentieth Century is littered with the unintended consequences of technology, from the disastrous physical impacts of cars, to the horror of nuclear weapons. I am by no means a Luddite (I love for instance, my e-bike and Apple Pencil) but I want to engage the tech sector in a manner that brings more criticality and interdisciplinary thinking to both their efforts and ours.”

Vishaan Chakrabarti

In the 21st century every detail is distilled. What is good, solid, meaningful, and beautiful; what can become part of nature and contribute to the natural balance; what is impartial and does not take the judgments of our peers and various -isms into account – this is what is valuable. I am not saying this is what is correct, because I don’t know it yet. Perhaps there is none, there never was. Or maybe one day big data will show us. Architecture is situated in the space between science, technology, and fiction. In this synthesis are three main responsibilities: to generate the right concepts, to focus on content, and to develop contextual points of views and solutions. We must at least be adept in making the following:

- Spatial/Programmatic Statement

- Structural Statement

- Material Statement

- Tech Statement

- Art Statement